I remember back in middle school and high school preparing for regional band auditions. Placement was based on a scoring system. Your overall score was made up of three categories: a prepared solo piece, scales, and sight-reading. The scales category, if I remember correctly, consisted of a few selected major scales (I believe full range, both slurred and tongued) and the chromatic scale. You didn’t know what the selected scales were going to be until the day of the audition. They were always posted on a list on a wall in a large auditorium. The chromatic scale always stressed me out. The options for the chromatic scale on saxophone were either to play it full range (Bb-F) or to play it two octaves starting on a provided note (C-C, D-D, F-F). The C-C and F-F chromatic scales feel very different under your fingers.

This is essentially what the chromatic scale meant to me back when I was a young musician. Basically, it felt like a test that simply showed how good I was at playing the chromatic scale. It seemed to have no relevant applications. Many years later, I have a very different opinion of the chromatic scale. The chromatic scale is a scale that takes some time to understand and appreciate.

So, now I’ve written about several scales used in jazz: the diminished scale, the whole tone scale, the altered scale, the blues scale, the augmented scale, the pentatonic scale, and the bebop scale. Some would call the chromatic scale a non-scale. It has no particular or obvious function. It’s just all twelve tones. But, it definitely has its place in jazz and improvisation. It has some unique applications. It also contains the building blocks for all other scales.

Scale Construction

The categories I’ve been using in my other jazz scales articles to describe how each scale is constructed and applied in music don’t quite fit with this scale. At least not on a superficial level. The chromatic scale’s construction isn’t difficult to analyze. It’s all the notes, in order.

The scale construction starts to get interesting when you look at different patterns built from the chromatic scale. When we practice the major scale, we practice it in different diatonic patterns: the major scale in thirds, the major scale in fourths, diatonic triads, etc. Similarly, we can practice the chromatic scale in chromatic patterns: major seconds chromatically, minor thirds chromatically, minor thirds in major seconds, perfect fourths in minor thirds, major sevenths in major seconds, diatonic triads in major seconds, etc.

When we practice this scale in different patterns, we begin to see more familiar scales in a new light. Remember symmetric scales? The chromatic scale is a symmetric scale. And chromatic scale patterns build the other symmetric scales. The diminished scale, whole tone scale, and augmented scale are built from the chromatic scale in chromatic patterns. When practicing the chromatic scale, you discover how the other symmetric scales are formed.

The whole tone scale is made up of major seconds in major thirds. Other chromatic patterns that create whole tone scale patterns include: major seconds in major seconds, major thirds in whole steps, tritones in whole steps, tritones in major thirds, minor sixths in whole steps, minor sevenths in whole steps, etc.

The diminished scale is made up of major seconds in minor thirds. Other patterns that create diminished scale patterns include: minor seconds in minor thirds, perfect fourths in minor thirds, tritones in minor thirds, major sixths in minor thirds, etc.

The augmented scale is made up of minor thirds in major thirds. Other patterns that created augmented scale patterns include: major thirds in minor thirds, perfect fifths in major thirds, etc.

Chord/Scale Relationship

Obviously there are not chord/scale relationships with the chromatic scale. Or rather, there’s just one chord/scale relationship: the chromatic scale fits over every chord. Knowing how to use the chromatic scale over a specific chord is a skill that just comes with experience. Although, there definitely is a methodology to it. I’ll go into more detail concerning different chromatic scale applications in the designated section.

Scale Patterns

Practicing the chromatic scale will make your improvising more versatile and more interesting. It will teach you how other scales are formed. But, even in non-jazz contexts, practicing the chromatic scale is just a beneficial thing to do. Working on the chromatic scale will free up so many technical hang-ups. There’s just something about being comfortable and totally fluid with playing chromatically. It will help with making something as simple as a fall sound way better.

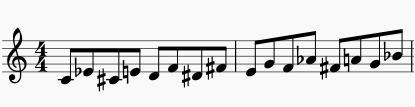

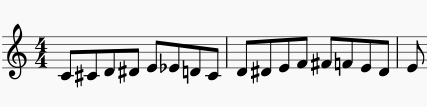

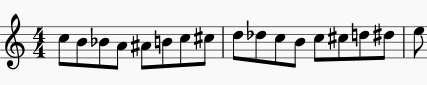

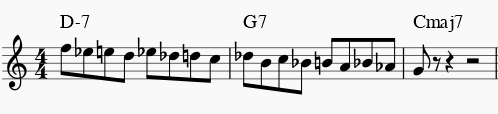

There are a lot of possible chromatic exercises you can practice. Here are just a couple.You should practice them full range, and then target areas that are the most difficult.

Application to Improvisation

The chromatic scale has both simple applications to improvisation as well as some more complex applications. There are some chromatic applications we do more or less innately. Then, there are some that take deliberate practice. Application of the chromatic scale to improvisation can fall into two broad categories: applying the chromatic scale in the context of another scale or chord, and applying the chromatic scale as its own chromatic idea.

When applying harmonic ideas or concepts to jazz improvisation, there are contextual and non-contextual applications. One way to apply the chromatic scale is in the context of another scale or chord. The simplest way is to use chromatic passing tones. This is the idea that led to the development of the bebop scale. There are plenty of ways to use chromatic passing tones. A few that work well are: 7 down to 5 over a maj7 chord, 5 down to 3 over a minor chord, and 3 down to 1 over a major chord.

If you’ve read my other articles, then you’ve already practiced contextual chromatic scale applications while working on the bebop scale. Using chromatic passing tones is a technique that comes naturally. It’s always been a defining part of jazz, especially since the Bebop Era in the 1940s. What makes the chromatic scale especially interesting in modern jazz, though, is applying it in a non-contextual way. This is something that takes deliberate practice and a discerning ear. When studying improvisation, we talk about tension and release. A way to achieve tension and release is by utilizing opposing ideas: slow vs fast, dense vs sparse, close intervals vs wide intervals, etc. With chromatic passing tones, we get the opposing ideas of diatonic vs chromatic. We can take that a step further. If we use the chromatic scale in a seemingly random way, it can create very strong tension. Then, if we resolve to a simple diatonic idea, it creates a strong release. I guess this could be called chaos vs order. This is an advanced technique that will come with time, but you can benefit from being conscious of it as a concept.

This first example uses the chromatic scale mostly straight and in a non-contextual way. It’s just a simple chromatic idea, making sure to not hit any ‘bad’ notes on downbeats. It looks as though it could be contextual, but it isn’t really. The notes in between the downbeats are technically passing tones, but there aren’t really any particular chords or scales that the passing tones are outlining.

This example uses a chromatic pattern, descending major seconds in descending minor seconds. This is definitely a non-contextual example. There’s not really any reason why it works or sounds good. It just does.

This example uses the chromatic scale in a couple different ways. The first five notes are clear contextual passing tones. The line descends from 5 down to 3 chromatically. The second measure is more like the first example. You could say the Bb-Ab is outlining 1 down to b7 of the tritone substitution and call it contextual. Really, it doesn’t matter how you analyze it. Experience and trial-and-error will tell your ears what sounds good.

One final application worth mentioning is using the chromatic scales in chromatic patterns. This application was used in the second example above (major seconds in minor seconds). As I mentioned earlier in the article, some of these chromatic patterns form symmetric scales. This isn’t really using the chromatic scale in a true chromatic sense, but you can discover some cool diminished, whole tone, and augmented scale patterns to apply accordingly.

Conclusion

I used to believe that one could eventually reach a certain point on his or her musical journey where scales don’t really exist anymore; where the chromatic scale is the only scale. A sort of musical nirvana. I don’t really believe this anymore, although I’m sure there are musicians that don’t think in the context of scales, so who knows. For me, personally, the chromatic scale has taught me a lot about musical harmony. I’ve come to many realizations while working on the chromatic scale.

I have another theory that jazz musicians turn to the chromatic scale when they’re (hopefully temporarily) bored with conventional harmony. This was kind of my experience. Classical music went in this direction at the turn of the 20th century. The chromatic scale is just totally free; no limitations. There are no harmonic or melodic constraints. Some chromatic concepts can get pretty involved, though. If you get bored with conventional harmony in jazz, check out George Garzone’s Triadic Chromatic Approach. Studying the chromatic scale will definitely give you new insights into music.

Thanks, Chris for nice sharing. Do I want to be more clear about a chromatic application?

Thanks for sharing nice information on music. Its really helpful for me.

These are really helpful to me. Thanks for sharing this.