Listening to Jazz Music

I have to begin this post with a disclaimer: this article may “ruin” listening to music for you. At the very least, it will change the way you listen to music, or at least set you on a path in that  direction; but I believe it’s a good direction. When I say it will change the way you listen to music, I mean it will make you listen to music in a way that most people do not. How do you think most people listen to music? This is something I don’t quite understand anymore. Different people grasp on to different things. How do you think people that are tone-deaf or rhythmically-challenged perceive music? Many people grasp on to the lyrics. If you understand the language, you understand the song. This is why a lot of people don’t enjoy listening to jazz or other instrumental music.

direction; but I believe it’s a good direction. When I say it will change the way you listen to music, I mean it will make you listen to music in a way that most people do not. How do you think most people listen to music? This is something I don’t quite understand anymore. Different people grasp on to different things. How do you think people that are tone-deaf or rhythmically-challenged perceive music? Many people grasp on to the lyrics. If you understand the language, you understand the song. This is why a lot of people don’t enjoy listening to jazz or other instrumental music.

Music is an aural art. As strange as it sounds, it’s easy to forget that these days. It baffles me when people post comments on a YouTube video asking for the “notes” or the “TABS” to some easy song that is being played. I guess I have some idea where this comes from. In many methods of teaching, the ability to read music is taught to be a very important, if not the most important, part of music. It is important, and the ability to read music well has been good for me in many playing situations, but it’s not the most important part of music. Many styles of music were improvised before the phenomenon of recording came about at the turn of the 20th century. Since recording didn’t exist, improvised music was written down. Today, many people play Bach transcriptions, rather than improvising or realizing the figured bass.

Music is a language. In spoken language, which do you think is more important: the ability to read or the ability to communicate?

In my own personal experience, since moving to New York, I’ve read very little music. A huge majority of my gigs are learned by ear. Listening to jazz and other music in a very focused way is necessary to my livelihood.

There are varying degrees of listening to music, but for the sake of this article, I’ll break it down into two categories: active listening and passive listening. Passive listening is what people do most of the time. They turn on some music while reading, doing homework, driving, working out, dancing, or maybe even writing a blog post. Passive listening takes no effort. It’s enjoyable. Listening to jazz and other music is supposed to be enjoyable. Music is entertainment. That’s its main purpose.

Active listening takes intense focus. It takes much more effort than passive listening, but is much more rewarding. It’s like the difference between leisure reading and studying for a test, or the difference between watching a blockbuster movie versus watching a documentary (not that documentaries aren’t enjoyable). The rest of this article will give tips and explain methods for getting better at active listening to jazz. Active listening can be trying to figure out the melody or chord changes to your favorite pop song, it can be trying to learn a drum part, or it can be transcribing a Clifford Brown solo. It’s even possible to listen to music actively without knowing much or anything about music. In a book I’m reading now, the author talks about transcribing lyrics to 80s hip hop (before you could find all the lyrics you would ever want on the internet).

Active listening takes intense focus. It takes much more effort than passive listening, but is much more rewarding. It’s like the difference between leisure reading and studying for a test, or the difference between watching a blockbuster movie versus watching a documentary (not that documentaries aren’t enjoyable). The rest of this article will give tips and explain methods for getting better at active listening to jazz. Active listening can be trying to figure out the melody or chord changes to your favorite pop song, it can be trying to learn a drum part, or it can be transcribing a Clifford Brown solo. It’s even possible to listen to music actively without knowing much or anything about music. In a book I’m reading now, the author talks about transcribing lyrics to 80s hip hop (before you could find all the lyrics you would ever want on the internet).

Passive listening is for the layperson. Active listening is for the musician.

This article will cover various techniques and exercises to help you learn how to listen to jazz and other music more effectively.

Form

An essential part of active listening to jazz is being aware of musical form. Different genres of music have different forms, although there is definitely some overlap. In classical music, we learn about Sonata Form, Rondo Form, Minuet and Trio, Theme and Variations, etc. If you listen to pop or rock music, there is usually a formula that goes something along the lines of: intro, verse, chorus, verse, chorus, bridge, chorus, chorus. Check out some of your favorite pop songs and see if you can hear this pattern. It makes learning music by ear a much simpler process.

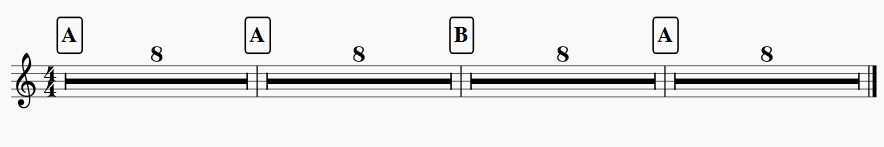

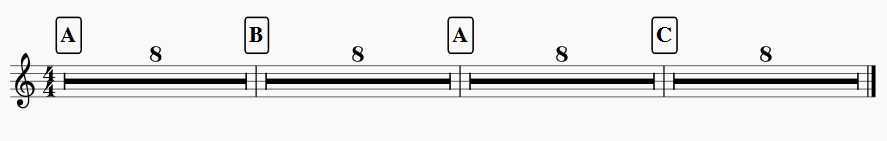

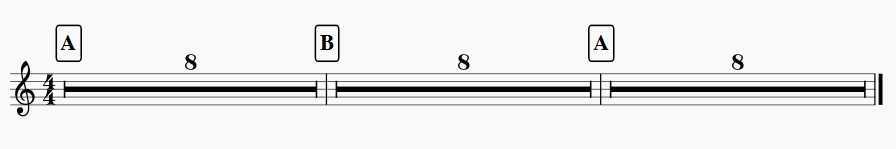

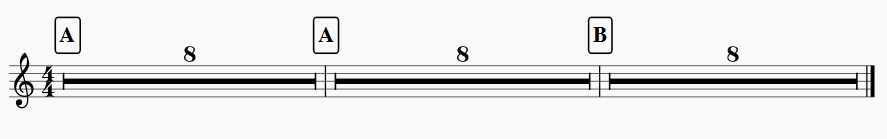

Likewise, there are a handful of formulae used in traditional jazz. Modern jazz can be more complex, since there is a lot of crossover from other genres, and many compositions are through-composed. For the purpose of this article, I’ll focus on traditional jazz. There are a couple of different types of form to be aware of when listening to jazz. The melody of each jazz tune has a form. The following are some examples of common song forms and jazz tunes that employ them.

Body and Soul, Don’t Get Around Much Anymore, Satin Doll, So What, Take the ‘A’ Train

All of Me, But Not for Me, I Got Rhythm, On Green Dolphin Street, There Will Never Be Another You

I’ll Remember April, Stablemates

Night and Day, Song for My Father

Billie’s Bounce, Blue Monk, Mr. PC, Now’s the Time, Straight No Chaser

These are a few of the most common song forms used in jazz, but there are plenty of other forms. Listen to a bunch of jazz tunes and try to decipher their song forms.

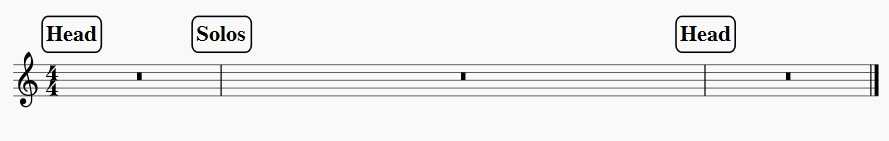

The melody of each tune has its own form, but jazz also has a larger form structure since improvisation is involved. Commonly in small group jazz (trio, quartet, quintet, etc.), the group plays the head (melody), then a few members of the group take turns soloing, and then they play the head again. The large form of a jazz performance could be something like: intro, head, trumpet solo, saxophone solo, piano solo, drum solo, head.

Traditional big band jazz has a similar form, but may have some added elements, such as solis and shout choruses.

Motivic Material

When you’re listening to jazz, being aware of the form provides a big picture understanding of the structure of a given tune. It’s a basic understanding of what you’re listening to, so the song doesn’t just sound like random noise (which is how music without words probably sounds to some people). Now it sounds like organized noise.

Beyond that, you can listen to each soloist individually to get some insight into how they think while improvising. As your knowledge of jazz theory and improvisation grows, you’ll be able to pick out and recognize more and more things in an improvised solo. Something you can listen for right away is motivic material and the development of this motivic material. We’ll look more at this later when I provide some examples.

Group Interaction

Something that is unique to improvised music is group interaction. When reading music from a page, there is little opportunity to be collectively creative as a group. Imagine a rock garage band  situation. You’re figuring out what the rhythm guitar and bass player are going to play, what the lead guitarist is going to play during the intro and when and for how long he’s going to solo, how the drummer is going to lead from the verse into the chorus, what the background vocals are going to be, etc. In this situation, writing music is a collective effort. In improvised music, you’re simultaneously doing this as you’re performing for a crowd. Improvised music is spontaneous composition and performance.

situation. You’re figuring out what the rhythm guitar and bass player are going to play, what the lead guitarist is going to play during the intro and when and for how long he’s going to solo, how the drummer is going to lead from the verse into the chorus, what the background vocals are going to be, etc. In this situation, writing music is a collective effort. In improvised music, you’re simultaneously doing this as you’re performing for a crowd. Improvised music is spontaneous composition and performance.

As with listening to individual soloists, your understanding and recognition of how members of a group relate and react to one another will grow as your experience grows. There are certain simple things you can focus on when listening to jazz. The soloist can decide to increase the intensity of his or her solo in a bunch of different ways. Maybe he or she plays louder, plays more notes, plays higher notes, etc. These are a few simple ways to increase intensity. The band will hear his or her intention and react to it by getting louder with him or her, playing more densely, etc. Another way the band can react is by simply responding to the material the soloist puts out there. Maybe the soloist plays a phrase and then leaves a couple bars of rest. This could be an opportunity for the piano player to play a phrase in response to what the soloist just played. The more comfortable a group gets playing together, the more they will understand each other’s preferences. That’s why groups that have been playing together for a long time sound so in sync with each other. Improvisation is musical conversation. For most people, conversations are usually more fluid with people you know well than with strangers.

Example – “Strasbourg-St. Denis”

Okay, now I’ll provide a concrete example to help you to understand the methods for listening to jazz detailed above. Take a listen to “Strasbourg-St. Denis” by the Roy Hargrove Quintet.

Utilizing the methods above, I’ll outline a few of the things I hear when I listen to the recording:

0:12 – Piano introduction. Bass and drums join.

0:47 – Trumpet and alto saxophone come in with melody. AAB form, listen for the conversational piano interjections during the rests in the A sections. Although the form is AAB, they don’t seem to always necessarily follow this form during solos, since the chord changes are the same for both section.

1:39 – Piano solo begins, intensity and volume drop, piano player mutes strings, drummer switches to closed hi-hat.

1:56 – Piano player plays simple one-note idea, something easy for the listener to grasp onto.

2:14 – Piano player plays another very simple motivic idea and develops it throughout the next eight bars.

2:31 – Piano player plays an idea and repeats it, starts off with muted strings then moves to use of all open strings, right and left hand play. Solo builds.

3:40 – The drummer finally switches to that open cymbal sound on the ride cymbal, an idea he hinted at several times since around 2:10. Piano player still using loads of motivic material.

4:11 – You can see the piano player signals it’s the end of his solo, something we can see in the video, but should also be able to hear.

4:14 – Trumpet solo begins, drummer goes back to hi-hat, piano player plays chordal textures, intensity drops but not as low as beginning of piano solo. Trumpet uses tons of motivic material, something that Roy Hargrove is a master of.

4:32-4:41 – Listen to this several times. Trumpet is playing great motivic material and leaving space in between for the piano player to respond.

5:07-5:19 – More of Hargrove’s masterful motivic development at the beginning of his second chorus. He takes a simple idea, repeats it, then rhythmically displaces it. What makes this even more interesting to listen to is that the theory of the idea is employed in the B section of the melody, and then he uses it in his solo.

5:59-6:11 – A very elegant way to build intensity, Hargrove plays one note, leaving sonic space for the rhythm section to take hold.

6:33 – Drummer switches to crash cymbal, once again delaying our gratification as long as he can.

6:50 – Trumpet is playing high notes, signifying a high point of his solo.

7:25 – This is one of my favorite parts of the recording. It’s a prime example of musical miscommunication between players. Not every miscommunication is necessarily someone’s fault, but in this case it seems to be the rhythm section’s fault, maybe the drummer’s fault. The drummer drops out like it’s the beginning of a new solo, while the trumpet player is looking to play eight more bars. In his defense, he could have thought the trumpet player wanted to drop the intensity for his last eight bars. Either way, the trumpet player went in one direction (way up) and the rhythm section in another (way down). Probably a lot of people missed this (the drummer fixes it pretty quickly), and more probably would have missed it if Hargrove didn’t look back and laugh at the drummer, but it’s pretty obvious to those who are practicing active listening to jazz.

7:42 – Alto saxophone solo starts, piano player drops out (to wipe forehead though, I guess).

7:59 – Drummer drops out, piano and bass hold down rhythm while drummer provides sparse textures, lowest point of intensity since the beginning of the song, saxophone plays accordingly.

8:36 – Saxophone plays one-note motivic idea. Would he have come up with this on his own or was he inspired by the piano player’s and trumpet player’s previous use of the same technique?

9:07-9:27 – Listen to that masterful motivic development!

9:45-9:51 – Listen to the tune “Diverse” in case you didn’t catch that.

10:26-11:03 – Saxophone player basically stays on this note forever, builds intensity through motivic simplicity. Gives room for the bass player to go crazy on the bass drum.

11:11 – Saxophone player goes up into that altissimo range, high point, goes down from there.

11:28 – Out head. They don’t play the B section.

There’s so much more to listen for in this recording, but these are some of the things that caught my attention. Maybe you can pick out some things that I missed. Each player on that bandstand is among the best in the jazz world. They each have intention and conviction in what they’re doing. It’s rewarding and humbling and fun to be able to get inside their heads and see what they were thinking when this was recorded.

Isolating Each Instrument

In addition to the exercises described above, there are more advanced ways of listening to jazz. I learned this next listening exercise while I was at Indiana University. It’s not necessarily a deeper form of listening to jazz than the methods described above. I’d call it a more directed approach. If you really want to get inside a specific track, then this is a great exercise.

This method involves isolating each instrument. You focus your ears to one specific instrument for the whole recording. During solos, instead of listening to what’s going on in the forefront (which is the natural inclination) you listen to what else is going on. This exercise takes a good amount of time and a lot of concentration.

There are a few different ways to do it, but here is a template:

1) Listen to the track as a whole

2) Listen to each soloist

3) Listen to the piano/guitar

4) Listen to the bass

5) Listen to the drums

6) Listen to track as a whole again

There are specific things you should be listening for. When listening to the soloist, you can listen for several things: motivic material and development, use of space, interaction, etc. When I say to listen to the piano/guitar, I mean to listen to what they do during the melody or during other solos. Listen to how they comp. Listen for sparse, one-note textures vs. large open-chord figures. Listen for when they decide to play vs. when they decide to lay out. For the bass, listen for when they walk in two vs. when they walk in four, listen for what range they decide to play in. Listening to the drums can be several listens on its own. You could listen for what textures drummers decide to use as a whole, whether they decide to play sparse or play busy, what cymbals they decide to use and when. You could spot listen to each drum and cymbal. Listen to a recording and only listen to what the drummer does on the snare drum the whole time, or the ride cymbal, or the bass drum, etc.

I planned on writing out another example to illustrate this method, as I did above, but listening to jazz in this way can be very involved and detailed, and it would take a whole series of dedicated articles to do any recording any sort of justice. I recommend using this method while listening to “All Blues” from Kind of Blue and seeing what you hear. Also try it with some of your favorite recordings. You’ll hear things you never heard before, and it will give you a deeper appreciation for your favorite music.

Conclusion

The material and techniques described above provide an introductory method of listening to jazz. You will definitely get better as you learn more and become a more experienced player, but the methods above offer some tips and tricks to send your ears in the right direction. Moving forward, I highly suggest you pick up whatever seminal jazz recordings you can find and actively listen to them as much as possible. I understand that passive listening is easy and enjoyable. I listen to more than my fair share of pop music to clear my mind. But, since music is an aural art, there is a lot that can be learned from deep listening.

Active listening is a necessary part of becoming a better musician. Set goals for yourself. Maybe you want to actively listen to one complete jazz album a day, or actively listen to jazz for one hour a day as part of your practice routine. The more you do this, the more music will mean to you. My disclaimer at the beginning, when I said that this article may “ruin” music for you, I meant that eventually you won’t be able to listen to jazz without at least subconsciously analyzing it. When writing these blog posts, there’s no possible way I could be listening to jazz. I’m not that great of a multi-tasker. I wouldn’t be able to focus on writing. But it’s worth it. Because I have this deep understanding of music, I can provide entertainment for everyone who enjoys listening, whether they like to listen to it as a feel good music, dance to it, or analyze it. Maybe I should use the word “upgrade” instead. This article will “upgrade” the way you listen to music.