On November 13, 1940, influential film critics and Hollywood notables gathered in New York’s Broadway Theatre for the premiere of a groundbreaking film – Disney’s original Fantasia.

Edwin Schallert of the LA Times declared the film to be “courageous beyond belief.”

Isabel Morse Jones labeled the movie as an “”enormously varied concert of pictorial ideas,” and Bosley Crowther of the New York Times claimed that “motion picture history was made last night.”

Crowther couldn’t have been more correct.

Despite complaints from crusty music critics and grumbles from composers like Igor Stravinsky (the only living composer whose work was featured in Fantasia), Fantasia achieved monumental success, and it nudged the relationship between classical music and cartoons from a friendship into a full-blown romance.

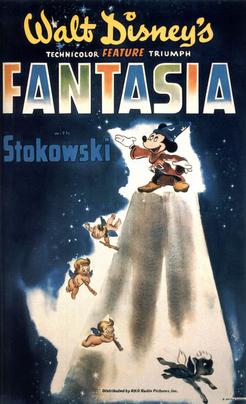

Fantasia was visionary. Just look at the fantastic minds that created the project: Walt Disney, Leopold Stokowski, and Deems Taylor.

Not long after Fantasia’s inception, other animation greats like Michael Maltese and Chuck Jones started pairing classical music and cartoons too. Fantasia took animation–generally considered a humorous art form–and merged it with a historically serious genre in a way nobody could have imagined.

Nobody except for Walt Disney, of course.

From The Band Concert to The Sorcerer’s Apprentice

In 1935–during the heart of Disney’s decade-long run with his Silly Symphonies*–Walt Disney decided to try something new: He conjured up a 15-minute short called The Band Concert.

In the episode, Mickey Mouse played the part of conductor, and Donald Duck and Goofy were among the many familiar faces in the band itself. But although the short film was highly acclaimed for technical reasons, its use of Rossini’s William Tell Overture set the standard for using classical music in cartoons.

Following The Band Concert in 1935 and the conclusion of Silly Symphonies in 1939, Walt Disney decided to revitalize the “career” of his most famous character, Mickey Mouse. His strategy?

The Sorcerer’s Apprentice.

Disney set The Sorcerer’s Apprentice to Paul Dukas’ tone poem of the same name, and the only thing left was to find a prestigious conductor to lead the studio orchestra; fortunately for Walt Disney, he happened upon a meeting with one of North America’s greatest classical musicians in a Hollywood restaurant soon thereafter.

Walt Disney Meets Leopold Stokowski

Walt Disney certainly didn’t intend on running into Leopold Stokowski, conductor of the Philadelphia Orchestra, as he sat down to dinner at Chasen’s Restaurant in Hollywood that evening in 1937. Fate had plans for the two creative visionaries, however, and as they talked about Walt Disney’s latest explorations into a music/animation hybrid, Disney became “all steamed up over the idea of Stokowski working with us,” he later wrote. Stokowski returned the enthusiasm.

Stokowski was also “steamed up” over the idea of putting classical music in cartoons. He loved it so much, in fact, that he offered his conducting services for free, and after the success of the initial Sorcerer’s Apprentice project, Stokowski agreed to sign on for a feature-length movie with the same goal — to pair great classical works with animated moving pictures.

But what if the subject matter was too profound for American households? Could an audience enjoy a feature-length cartoon set to a classical score if they didn’t already know the music? Stokowski and Disney agreed that a well-known, successful host was in order.

Music Critic Deems Taylor Would Introduce Cartoon Fans to Classical Music

Deems Taylor found success as a composer in the first half of the 20th century–his first professional composition gig was a commission by the Metropolitan Opera–but his lasting fame arose from his work as a commentator and critic.

He labored as Music Critic for the New York World throughout the 1920s, and he even held the post of Editor for Musical America for two years.

The pivotal moment of Taylor’s career, however, came while he was performing radio commentary during intermission of a New York Philharmonic concert; Walt Disney, then mulling over whom to cast as the “host” character in his yet-to-come Fantasia, heard one of the broadcasts. He was sold on Deems Taylor.

Within a few days of a phone call on September 3, 1938, Deems Taylor had traveled by rail to Hollywood, where he began to enthusiastically compile a program for Disney’s new motion picture.

The Finished Product

After extensive collaboration and trial and error, the three leaders of the project arrived at the following program for Fantasia:

- Toccata and Fugue in D Minor by Johann Sebastian Bach: In Leopold Stokowski’s words to Disney, “The Toccata starts off with three phrases which are like the playing of immense trumpets to call you to attention. For that reason, this composition is a wonderful selection with which to begin your picture.”

- Nutcracker Suite by Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky: The programmatic nature of Tchaikovsky’s holiday season masterpiece provided a perfect way to feature classical music in cartoons.

- The Sorcerer’s Apprentice by Paul Dukas: It was only fitting for Mickey Mouse as the Sorcerer’s Apprentice, the idea that kicked off the whole idea in the first place, to be included in Fantasia.

- Rite of Spring by Igor Stravinsky: Disney, Stokowski, and Taylor initially chose Stravinsky’s Firebird, but Rite of Spring proved to be a better fit in the end.

- The Pastoral Symphony by Ludwig van Beethoven: Disney’s team was attracted to the mythical inspiration behind Beethoven’s Symphony No. 6.

- Dance of the Hours by Amilcare Ponchielli: This work provided some much-needed “comic relief” to a soundtrack weighted towards more serious music.

- Night on Bald Mountain by Modest Mussorgsky: Disney chose one of Mussorgsky’s most dramatic works here — it’s full of demons, magic, and yes, the Devil.

- Ave Maria by Franz Schubert: This choral rendition provided the perfect atmosphere for the animated Roman Catholic imagery during this section of Fantasia.

The Philadelphia Orchestra recorded the Fantasia soundtrack in the spring of 1939. Stokowski conducted, and the orchestra played in their usual concert hall (at that time), the Academy of Music on South Broad Street.

Most film critics loved the insertion of classical music in cartoons, while some prominent American classical musicians and composers, on the other hand, reacted negatively to Fantasia.

Stokowski’s arrangements and orchestrations drew specific criticism from the likes of Virgil Thompson and others. The effect of these petty criticisms was negligible however–Fantasia was a huge success.

Even though Fantasia’s 1940 premiere came during a hard time in US history, the lasting quality of Disney’s classical music excursion was not lost on the American public. It remained a classic throughout the entire 20th century, and it even scored a sequel in the year 2000.

Fantasia’s Impact: A Legacy of Classical Music in Cartoons

Walt Disney’s love for classical music, which really came to light in 1935 with The Band Concert, helped create one of the most influential pieces of animation in film history.

By presenting the music in an artistic and serious way (while also having plenty of fun with the movie), Disney introduced famous classical works to an audience that wouldn’t have listened to them otherwise.

In addition to promoting classical music, Disney also kicked off an era of classical music features within cartoons; the reign of Chuck Jones and Michael Maltese (Herr Meets Hare, the Rabbit of Seville, Etc) was right around the corner.

Before Warner Bros. became the foremost purveyor of classical music in cartoons, there was Disney, taking risks in film that Edwin Schallert could only describe as “courageous beyond belief.”